Xu Zhen’s Interview by Andrew Maerkle at the occasion of MadeIn show at Long March Space

The path of Appearance is Always by Andrew Maerkle

It would be misleading to say that Xu Zhen is one of China’s leading young conceptual artists. Born in 1977 and based in Shanghai, Xu has been active as a multimedia artist and curator for over a decade now since graduating from the Shanghai Art and Design Academy, a technical college, in 1996. A co-founder in 1998 of the influential artist-run space BizArt Art Center, he has also organized seminal exhibitions including 1999’s “Art for Sale,” staged at a Shanghai shopping mall. As an artist Xu revels in tipping over the sacred cows of social convention. He has made installations of oversized tampons and vitrines – mocking British artist Damien Hirst – containing a life-scale model dinosaur split into two halves and suspended in formaldehyde. For the multimedia work 18 Days (2006), Xu traveled to China’s border territories and staged military invasions into neighboring countries using remote-controlled tanks, planes and boats, while in An Animal (2006), the artist filmed a panda-like creature undergoing assisted ejaculation. Perhaps the artist’s best-known work to date, the multimedia installation 8848-1.86 (2005) documents a fictional but almost credible expedition to chop off a man-sized chunk from the peak of Mount Everest, and comes complete with the result of the expedition displayed in an gigantic, refrigerated trophy case.

In 2009, Xu announced that he would stop practicing as a solo artist and instead operate under the company name MadeIn, working in collaboration with a staff of over 10 other artists, technicians and coordinators. This move has expanded the diversity of genres that Xu employs, and one of the company’s first projects was to produce a series of works, ranging from paintings and sculptures to installations, purporting to have been made by contemporary Middle Eastern artists.

In MadeIn’s current exhibition at Long March Space in Beijing, “Don’t Hang Your Faith on the Wall,” works named after quotes by famous intellectuals parody long-established approaches to minimalist and conceptual art. ART iT met with Xu Zhen at his studio in Shanghai as he was preparing for the Beijing exhibition to discuss topics ranging from the performance of spectatorship to the international fascination with Chinese contemporary art and the question of what defines ethics.

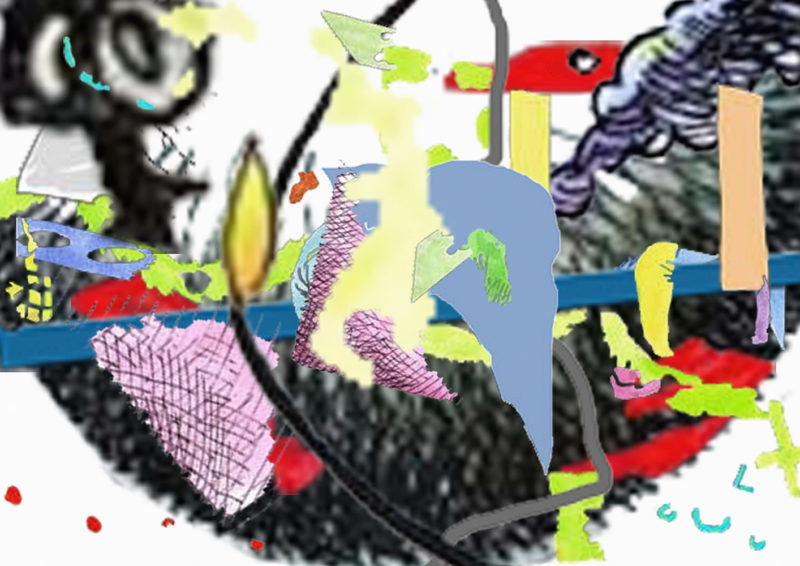

Unification is a reductive process rather than a process of gain, in which loyal believers never feel complete or secure. (2010), acrylic on canvas, 150 x 159 cm. Courtesy the artist and Long March Space, Beijing.

ART iT: You recently stopped working as a solo artist and have now established your own company, MadeIn, through which you produce works. What was the motivation for that development?

XZ: I’ve always made a wide range of works and projects, so I thought it would be better to consolidate everything under one name. MadeIn is very similar to an advertising agency. I am like a CEO. I give my staff an assignment, they go back and come up with proposals and then I review them, decide what works, play around with them, add to them, recombine them, and come up with a finished product that could be completely different from where it started. Because we are all working for a company, we can communicate and collaborate directly. It’s much more straightforward than a collaboration between two individual artists. Nobody’s keeping tabs on degrees of authorship.

I think a good way to look at it is that great works are something you discover, not something you create. I feel I would be limited in what I could discover if I were working on my own.

ART iT: Since you started MadeIn do you ever make works yourself?

XZ: Never. Even before, I rarely made my own works. Usually I’d come up with an idea and then find someone to produce it for me. Now for example I’m composing works on the computer and then my staff paint them for me.

ART iT: What’s the difference between what you’re doing and someone like Zhang Xiaogang, who has a studio full of assistants making his paintings?

XZ: I feel the bulk of “Chinese painting” is not art. It’s purely commercial product. There was a moment in history when those artists actually were making significant contributions, but now they’ve strayed from the idea of art itself.

We feel that MadeIn is fundamentally different. The works we make are a satire of the market. Of course we are also aware that they will become commercial products that circulate in the market. There’s a conflict there, but we hope that the project can maintain several different directions that coexist at once. Some works will be directed at the market, others may be more academic and completely unmarketable. So to the extent there are conflicts in our aspirations for these projects, we actually embrace those conflicts.

ART iT: What was the idea behind MadeIn’s “Middle Eastern Art” project, in which works drew heavily upon clichéd images and materials associated with the Middle East?

XZ: For us the whole Middle Eastern art project was a kind of performance. We were playing with relationships of active looking and objectification. We wanted to see what would happen when we added a third culture into the dynamic of two cultures – China and the West – mutually regarding each other. So if the West is looking at China, and China then looks at the Middle East, when we make works that are supposed to be “Middle Eastern,” are those works intended for a Chinese audience, or are they intended for a Western audience?

Anybody who sees the Middle Eastern series will either think it meets their expectations or it doesn’t meet their expectations. This reaction is partially determined by the viewer’s own experiences, and so what we were trying to address were the issues behind how expectations construct viewpoints.

ART iT: One interesting thing about Chinese contemporary painting to me is that even certain established artists will make one series of work for a few years, and then make a completely different series three years later, with no apparent stylistic or conceptual relationship between the two. So such artists seem to be seeking change for the sake of change. Then of course as you say your own works vary widely.

XZ: I understand what you’re getting at. It’s related to the art system in China, which allows artists to get away with anything. Why is that? First, we lack critics. And then we also lack a structure for artists to mature. The opportunities I have as an artist are not so different from those of someone who is 20 years old now. In terms of criticism, discussion, theory, it’s all the same. There is no support for established practices.

And because there are no standards – no one to say what’s good or not – it’s easy for artists to think that they can make one kind of work one day and a completely different work the next. Artists of my age have all come through this.

Ultimately I feel that contemporary art in China, in terms of method, execution, conceptualization and depth, is too simplistic. The attitude is, “make it however you want to make it.” We lack the kind of knowledge to discuss issues deeply, and I honestly feel it’s a problem affecting all of the art here. I would argue that in my own works though there is a clear line of thought that links them together.

ART iT: Yes, and I suppose you could also turn the situation on its head and say that the lack of structure allows artists in China an enviable freedom. Is the fact that you didn’t attend a higher-degree art school a positive for you?

XZ: I’m glad that I didn’t go to university. Now that I am aware of the kinds of things they were teaching at that time, at the very least I can say it wouldn’t have suited me.

ART iT: But you have also been involved in the establishment of artist-run spaces like BizArt Art Center and Shopping Gallery. What is the appeal of curation for you?

XZ: I enjoy it. I don’t think artistic production is limited to making works. It can also be discussion, curating exhibitions, making publications. I think creativity should develop in all directions. For example the experience these past few years running BizArt has helped me both as a curator and as an artist. And sometimes when you’re making a work it’s more like you are curating or preparing the work than physically making it.

As a curator, every time you apply yourself to organizing an exhibition, your own ideas change as well. This opportunity to reconsider your own thought process, or to move across different degrees of thought processes, is the most interesting part of curation for me.

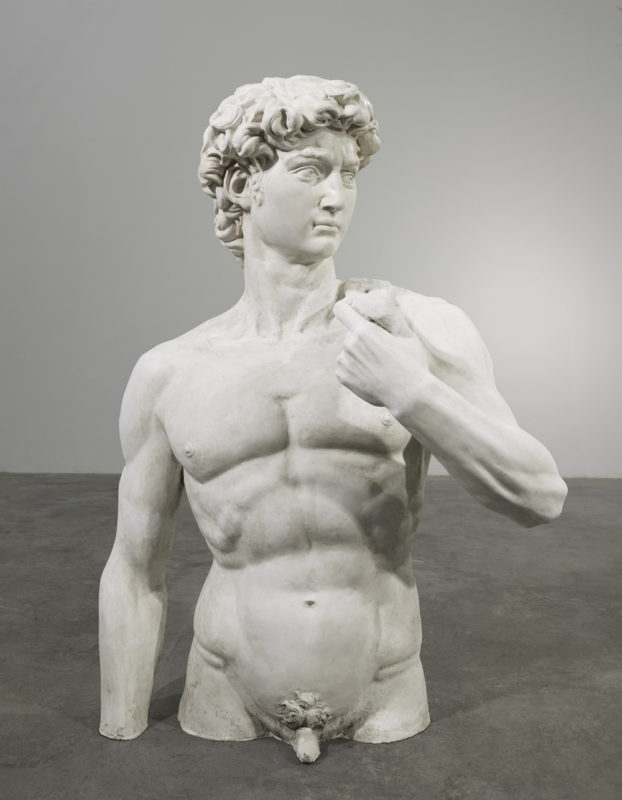

The people is a beast of muddy brain. It does not know its own force; it only knows

absolute obedience. (2010), marble, 180 x 100 x 80 cm. Courtesy the artist

and Long March Space, Beijing.

ART iT: In 2006 you worked on the exhibition “The Real Thing: Contemporary Art from China” at Tate Liverpool, which seemed to be one of the more focused China surveys to take place in Europe and the US in recent years. What was that experience like?

XZ: There were two other curators, Karen Smith and Simon Groom, and I was just helping them out. The exhibition was in fact a rather typical “cultural tourism” project. My contribution was simply to make a list of artist recommendations, because there was no room in the exhibition framework to address substantial issues. These culturally oriented exhibitions always come out being somewhat politically correct or promotional, so they’re not interesting to me, although I don’t have a problem helping out if I’m asked.

ART iT: Does that reflect your general opinion about the phenomenon of China surveys in Europe and the US?

XZ: This is precisely why we wanted to do the Middle Eastern Art project. People have preconceptions about the world, and often see the things they want to see, or find what they want to find. I’ve always been apathetic toward the China surveys. And now I have no interest in such exhibitions whatsoever. As an artist you say, “OK, if there are several different kinds of exhibitions, then this is only one of them and it’s not the most important.”

I’ve declined to participate in many such exhibitions because they’re just too limiting. This includes even exhibitions taking place in China surveying the history of Chinese contemporary art, for example shows about the past 30 years of art in China, or the past 30 years of painting, and so on. The curators take an egoistic approach to documenting these histories, rather than maintaining a detached perspective. It makes me uneasy.

ART iT: How do you feel about the idea of a history of Chinese contemporary art, has it already been established or is it still undergoing formation?

XZ: There is already a history here, but it’s not very significant. There has been a lot of discussion about this situation recently. Over the past 35-odd years of Chinese contemporary art, there have been four or five major figures, and each of these figures maintains their own set of historical values, and even today those values tend to be self-centered or, perhaps, domestic. Of course China is still developing, but there are very few artists here who are thinking about producing something that could be of value or significance to the international context. Commercial artists like Zhang Xiaogang may have been significant in the 1980s and ’90s, but I feel that as history has changed, and the environment has changed, they haven’t changed at all. Or rather their change has been to turn art into commerce.

ART iT: How do you feel about international art?

XZ: Well, I’m also frustrated with international art. Everybody seems to be reviving relatively old concepts, including relational aesthetics and multimedia art – even someone like Isaac Julien. After the opening of his show at ShanghArt Gallery for his new installation Ten Thousand Waves, which was filmed in China, I went to dinner with other artists and we felt that the work was very mainstream, very “correct.”

ART iT: Can you explain more about your impressions of Ten Thousand Waves?

XZ: My first impression was that it was superficial in its use of images of China, then I thought there’s no way an artist like Isaac could be so superficial. After watching the whole thing I realized it’s not the work itself but the issues that Isaac wants to discuss that have been simplified. Issues of immigration, or the issues that arise from the process of people seeking their livelihoods – issues of reality, life, history, social reform; these are some of the most pressing and conflicted problems in China today. So my personal outlook is that Isaac has found a way to tell his own story, but that story is a little simplistic.

ART iT: You mentioned that your recent work is a satire, but in one sense satire can be just as superficial as something that is commercial or simplistic. What kind of relationship do your works have between surface and depth?

XZ: The relations are constantly changing. At times you are dealing with a relatively concrete issue of audience, at times you’re dealing with a systemic issue, and sometimes that systemic issue is grounded in concrete reality, other times it’s about the art system. For MadeIn right now, it’s possible to turn all those issues into art; the distinction lies in whether there is any effectiveness to that. Our biggest concern right now is the question of how far we can take those issues. How can we express an idea, and why do we want to express it?

ART iT: Have your works changed much over the years? It seems like they could roughly be organized into three distinct periods.

XZ: There are big differences in all the works. The early works were mainly instinctual. The middle period works were also instinctual but at the same time had a kind of method informing their production. The installation and video about the Everest expedition, 8848-1.86, would be one such work. It started from a very small intuition and then became something that could relate to social issues like how we believe in “facts.” Yet these works largely revolved around the content, and the method came later. In contrast, what MadeIn represents is a method, and not content, although we can still insert content into the methodology.

ART iT: One of your last solo projects was the installation The Starving of Sudan (2008) at Beijing’s Long March Space, where you used a live child to recreate the scene captured in photojournalist Kevin Carter’s Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of a vulture stalking a starving Sudanese toddler. What was the motivation for that work?

XZ: This work actually anticipated the Middle Eastern Art series. They are both about making the audience use their own knowledge to produce a judgment. So at Long March the audience were in the same role as Kevin Carter. They went to the show, took out their cameras, shot pictures and I’m sure were very excited. Then afterwards they could pass judgment on me – “Oh, this artist is no good.” And that parallels the fact that when Kevin Carter died, he was under a lot of pressure – condemned by the whole world; but the whole world does exactly the same thing that it condemns.

ART iT: As an artist do you have your own sense of ethics or morals?

XZ: I think I do. I have no idea where it is, but it should be somewhere. Ethics evolve along with your experiences, or as you gain more experience you discover new perspectives on the issues that you thought affected you. So it’s like the Kevin Carter piece. People have to decide where they stand. Am I part of the audience? Do I identify with Kevin Carter? Am I looking at it from the perspective of the people in Sudan? Actually it’s none of the above, but creating that kind of situation can prompt viewers to reflect on their own ethics. It’s not about fundamental values, it’s about questioning the nature of ethics, and I think this is the approach that suits me.

ART iT: Do you think that contemporary art has a function in Chinese society today?

XZ: Currently there is no place for contemporary art here, because in many ways it is still dependent upon developments in Europe and the US. But the emergence of the market, combined with increasing social problems, has helped to draw art and society closer. They are already closer than they were 10 years ago.

ART iT: What do you think is the possibility for the future of contemporary art in China?

XZ: I think it has a lot of potential. Otherwise I would stop making art.

Saw on Art it

Tags: 2011, Chinese artist, interview, MadeIn Company, Xu Zhen, Young Chinese Artists